Ink on Chinese paper, 200×200 cm

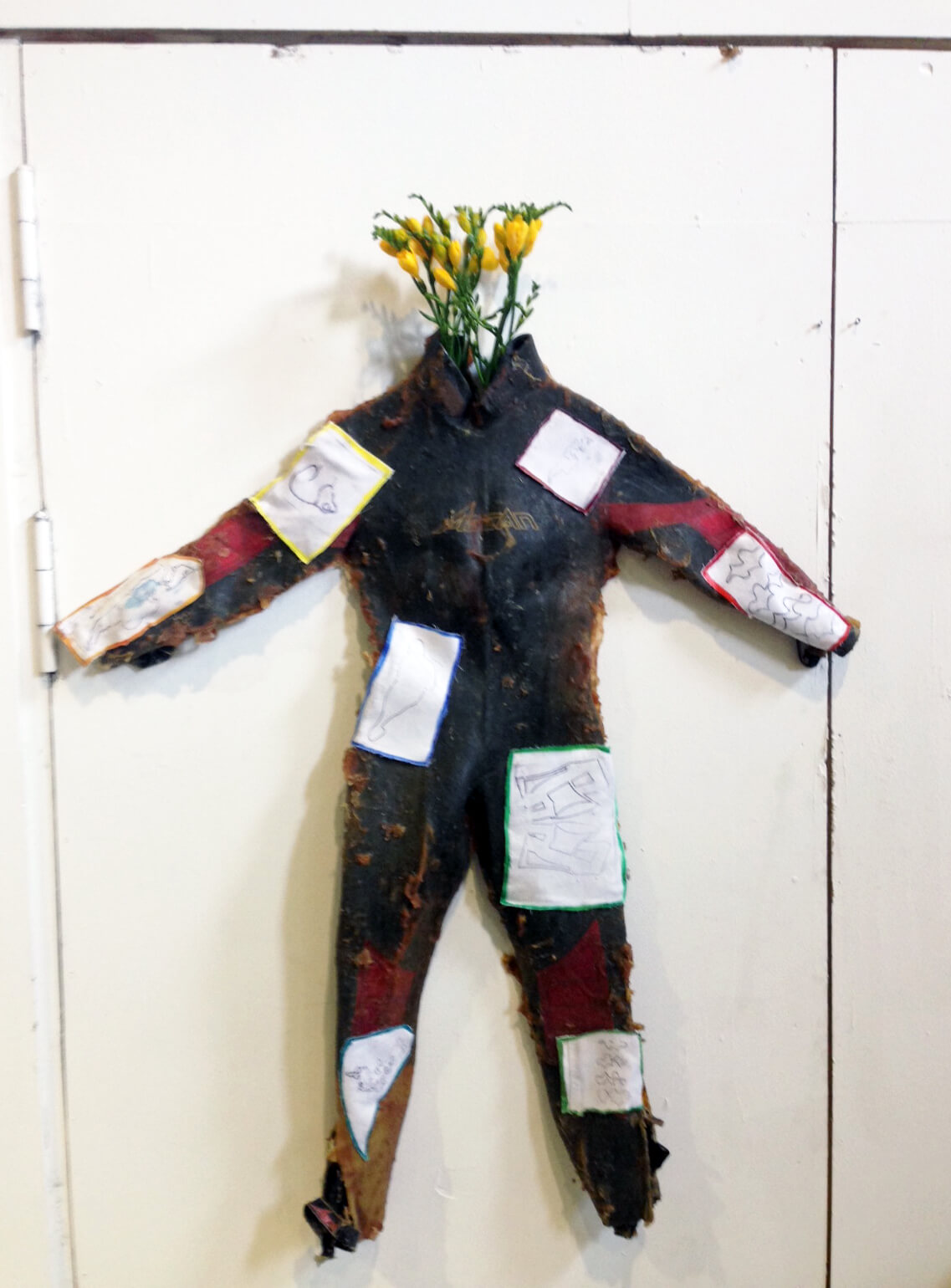

BODY, STRONG AND FRAIL

The first thing I happen upon in Susann Brännström’s study in southern Stockholm is a series of paintings whose motifs consist of a net of tense, bending lines. Are they structural markers of control, protection against an unspecified threat? Slowly, like an after-image, a vague void appears, assuming the shape of somebody’s back, a perpendicular centre for the blackness of the game of the lines. I fall prey to uncertainty; what can I make of all this? Seeming to sense my confusion, the artist provides me with a key. Yes, the game of lines can be seen as a sign of auxiliary constructions. The black, tightly laced lines strive to hold together and stabilise a fundamental yet fragile and exposed structure. The stylised motifs of the pictorial sequence convey a sensation of potential danger, physical as well as interior.

FORMAT AND MEDIUM

In Susann Brännström’s work two factors form a ground as stable as warp and weft in weaving. The formats vary between 122×122 cm squares and 244×122 cm rectangles; that’s the warp. Her medium is consistently Indian ink and tempera on paper or unworked wooden panels with visible grains: these might be said to correspond to the yarn. As for the rest, the paintings are devoid of associations with things woven. The motif is drawn in full scale on the ground and forms the basis for a painting. Drawing and colour are both linked to the surface of the picture, refraining from giving an illusion of depth. This is an artist who demonstrates the full expressive register of Indian ink technique. The drawing liberates the movement. Now the brush line demonstrates the flexible agility characteristic of a strand of hair or calligraphy, now it ripples like the scrawl of insect trails beneath the bark (as in Henri Michaux’s prints). Distinctly outlined forms appear replete with impenetrable blackness, while other forms be-have now like ominously swelling clouds of ink under water, now like hardly distinguishable, pleated, palely flowing damp stains, suggesting the shady side of paint.

The intensity of the tempera paint activates a ladder ranging from cold to heat, hunger and saturation, lust and pain. Tempera is narrative’s imaginative medium, its Arabian-Nights voice. I see and seem to hear a world of sounds whose lightly resilient, winged notes touch dull, rasping, fatly earthbound ones.

SIGNS, MOVEMENTS AND GESTURES

The patterns of the panels are indexical signs of nature. The grain designates nature in a 1:1 relation. Here the pattern is not drawn by a human hand. As a visual effect, the grain is not an expression of a fantasy about nature, but it does convey an idea about nature. In the veined panels meeting with the tempera paint unexpected effects arise. A large, soaring yellow figure makes the wooden surface clearly suggest lilac! The bulges and furrows of the figure resemble happily fermenting flesh or saffron dough painted as graffiti; an example of the associative, symbolic signs of fantasising.

The veining of the wooden surface may of course seem to resemble other phenomena than the veining of wood. For example, stylised faces or river systems or pictures of maps. But the map works indexically, pointing to a model. Maps indicate details and their positions in a terrain; the more accurate they are in relation to reality, the better. It might be possible to see the whole of Susann Brännström’s pictorial world as a continuous mapping of the artist’s observations and reflections faced with the constantly on-going reality around her.

The physical traces produced in the act of painting on canvas or paper are also indexical signs; signs of the very idea of painting. They are the direct effects of a specific act which had resulted in a painting through more or less free gesturing (think of Jackson Pollock’s method of ‘spontaneously’ spreading paint on canvas). In its concrete aspect Susann Brännström’s painting points to the traces of its coming-into-being, deliberate, considered, methodical traces of movement and gesturing. When these traces assume a figurative form, we are free to interpret them as symbolical signs, as components of an un-written tale.

The forms on Brännström’s boards and sheets of paper seem to emerge organically from invisible sources, freely and of their own force. This procedure probably manifests itself most clearly in the magnificent painting of something that resembles a coral reef with many ramifications, monochrome under the water surface, palely shining over the surface where a metaphorical radiation awakes nature to sensations of colour.

FIGURATION, FEELINGS

The world of figuration occupying the painted surfaces may make us think of phenomena as diverse as toys with complex mechanics, Chinese sign codes for dreamlike landscapes (and the draughtsman Arthur Rackham’s knotty trees in the High Culture fairy-tale tradition from the turn of the twentieth century), the complex choreography of humans and microbes respectively, children playing with colourful modelling clay. Here are rhythms in mirroring, symmetrical balance with small displacements and dramatic movements towards departures, fragile nuances and sharply cut angles which, like a superior principle, break into and regulate the composition’s display of free dynamic dance. It soon dawns on me that this world of cryptic signs and figurations — sometimes staged in the most obscure pictorial spaces, sometimes pulsating with undisguised radiance — are conveyors of emotions. But what kind of emotions, and which ones?

Painting is language, an instrument operating with signs entrusted with the task of conveying emotions as a response to reality, the artist points out, informing me that what preoccupies her is giving expression to forms of human existence and potential of power, seen as a means of staging various primary states of feeling such as desire and shame, grief and joy, pain and pleasure, desire… What is at stake is creating a language valid both for oneself and for others. Yes, an imagery that appeals to the viewer, challenging her to meet the painting halfway and listen attentively to its signals. A language that invites the viewer to avail herself of the ability of empathy of her own body and her imagination and respond to its rhythms and movements and to a sensuality that sometimes allows itself to accept and affirm grossly vulgar overtones.

PROGRESSION

But faced with one of the paintings my thought is struck dumb. I discern a formlessness of reds and blues that have gone out, a bagginess crowned by a despairingly yellow spot (The Last Piece). This is the sign of a sack containing all colour, but with tones that have died away because of lack of light. Once more the artist comes to my succour. Here the artist felt a need to reset the brilliance both of the colour and of her own technique. A need to “stammer in one’s own language” for the purpose of giving room to uncertainty and concern. What does it mean to be human in our time and in the world we live in; how can we go on when ethical structures threaten to collapse?

The philosopher Gilles Deleuze formulates an image: “the smooth and the rippled room”. This image serves to demonstrate how we use different perspectives. Some people prefer the secure unequivocality of the rippled trace, others the mobility of a room whose perspective is kept open and wide. The task now is to “transgress the massive and global opposites in the direction of the underlying, vibrating molecular intensities” [1]. This insight might be formulated in a more accessible way but hardly more persuasively.

Download catalog PDF here.

- Sven-Olov Wallenstein, “Kommentar till nomadologin”, Nomadologin. Skriftserien Kairos nummer 4,

Kungl. Konsthögskolan och Raster förlag, Stockholm 1998, p. 187.

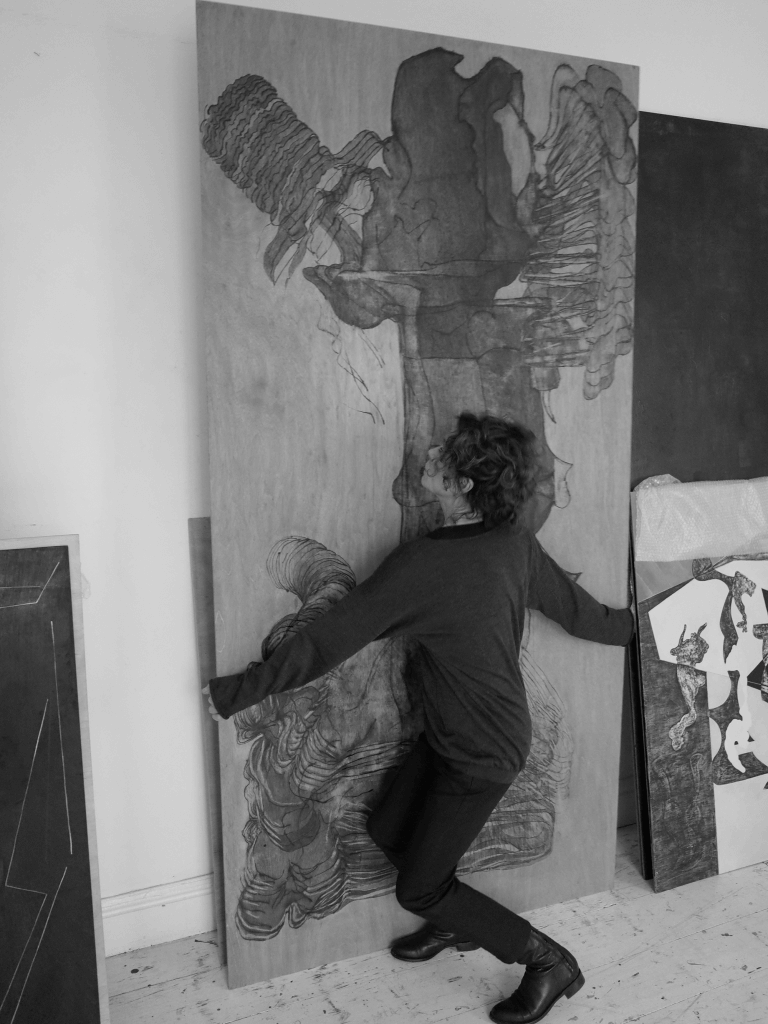

Susann Brännström in her studio

Susann Brännström in her studio